2020 IRWGS Prize Winners Announced!

Congratulations to this year’s IRWGS Prize Winners

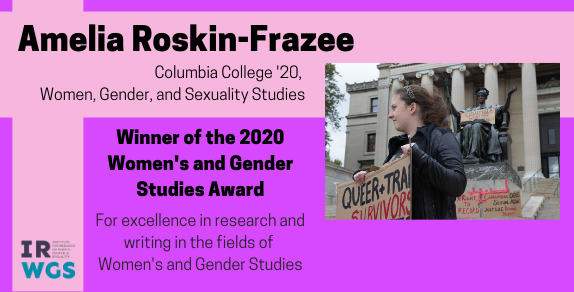

Eliza Siegel (BC ’20, American Studies) and Amelia Roskin-Frazee (CC’ 20, Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies) both winners of the 13th annual IRWGS Women’s and Gender Studies Award.

Their winning essays are titled “Jews-as-Syphilis: Metaphor, Science, and Tenuous Reality in Nazi Germany” and “Offending the State: The Gendered and Racialized Violence of the Sex Offender Registry.”

Emma Rosner (BC ’20, Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Human Rights), winner of the 25th annual IRWGS Queer Studies Award for their winning essay, “We have all participated”: Abu Ghraib, Homonationalism, and the Rationalization of Modern Torture.”

David Ehmcke (CC ’20, English and Slavic Studies), winner of the 3rd annual Feminist to the Core Essay Award for his winning essay, “To Tune the Ear Toward the Celestial: Techno-Musical Innovation and Feminist Mobilities in the Long History of Musical Expressionism.”

We interviewed the students to learn more about their work and their plans for the future.

1. What inspired you to focus on your topic for this submission?

I took Professor Rebecca Jordan-Young’s class “Sexualities and Science” at the same time as I was researching my American Studies senior thesis last semester. In both spheres of scholarship, I found myself drawn to the intersections between science and metaphor, myth and history, and aesthetics, race, gender, and nationhood. My thesis research on fascism and fascist aesthetics led me to make a small discovery about how the Nazis rhetorically linked an outbreak of syphilis to Jews through the use of scientized metaphor, weaponizing race science doctrines and anxieties around miscegenation to essentially make syphilis “Jewish.” What became increasingly apparent through my research was not only the long history of the racialization of disease for the purpose of consolidating and perpetuating hegemonic white power (a pattern which has reappeared in current efforts to transform Covid-19 into the “Chinese Virus”), but also how easily myths and metaphors can become concretized—how the realm of the figurative can manifest tangible violence and even genocide when it takes on the veneer of scientific “objectivity.”

2. How have you been able to integrate your interest in women’s studies in the work you have done here at Columbia/Barnard?While I unfortunately did not take advantage of many of the wonderful WGSS classes offered at Barnard and Columbia during my four years, women’s, gender, and sexuality studies scholarship has been foundational in nearly every research project I have undertaken. More than this, however, it has given me a way of looking at and reading scholarly texts and the world around me that is at once more critical and more generous than I could have ever imagined. I have been particularly lucky during my time at Barnard to have a community of dear friends who enact the subversiveness and optimism and criticism of queer theory into embodied practice through their dance, art, writing, and ways of engaging with others. I would like to thank my friends and professors who have taught me challenging and expansive ways of pursuing scholarship, activism, creative work, and community care.

3. What are your plans for the future?

I’m not entirely sure what the future holds, especially because of the chaos of the pandemic. But I am ultimately interested in storytelling with an eye on social justice, whether it be documentary filmmaking, investigative journalism, or podcasting. I may try my hand at farming and will probably go to grad school, though when and for what, I don’t know.

1. What inspired you to focus on your topic for this submission?

All the way back in University Writing, I was going through a policy document from some LGBTQ+ legal organization and noticed the sentence, “LGBTQ youth are more likely to be labeled sex offenders than non-LGBTQ youth.” There was no citation. Since then, I’ve been on a multi-year quest to research the subject. When I learned about the case of Leticia Garcia, a queer woman whose gender non-conformity in her mugshot photo became evidence in her sexual assault trial, I knew I wanted to learn more about how race and sexuality inform the Sex Offender Registry.

2. How have you been able to integrate your interest in women’s studies in the work you have done here at Columbia/Barnard

Honestly, some of the times I’ve integrated my interest in women’s studies the most has been in activism outside of class. I’m an organizer with No Red Tape Columbia, which is an intersectional anti-sexual violence group on campus. Our demands are rooted in an understanding of gender and power, and how gender intersects with other identities like race, ability, and immigration status. I am also a Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies major at Columbia, so most of my coursework has naturally revolved around these topics.

3. What are your plans for the future?

In the fall, I’m heading to UC Irvine to get my Ph.D. in Sociology. I’m planning to continue to research identity and incarceration.

1. What inspired you to focus on your topic for this submission?

I think the most concrete answer I can give is that my interest in modern torture stemmed partly from Silvia Federici’s incredible book Caliban and the Witch, which I read a while back in Professor Alex Pittman’s class Historical Approaches to Feminist Questions. In her book, Federici explores the connection between the transition to early capitalism in Europe and the torture and execution of thousands of accused witches. She discusses how, in that setting, torture was used as a way to reshape the formerly feudal society into a new capitalist one, in which people who had been subsistence farmers were forced to become disembodied laborers, beholden to a larger, mechanical system. Those who were accused as witches were often women who were seen to be useless as laborers or who remained tied to the old economic system. In effect, torture of accused witches was a way of reshaping people who were not considered useful, in the image of capitalist productivity. (This summary really doesn’t do the book justice; it’s been a little while since I read it.)Torture is something that is 1) rarely discussed or even acknowledged openly in the context of the US, and 2) usually explained as a tactic for extracting confessions. But it’s been known since the era of the witch hunts in Europe that torture is not an effective or reliable way to extract confessions. So I think what Federici explains, which is so important, is that torture is actually used as a way to reshape individuals and societies or forcibly instill certain lessons or desirable traits. There have clearly been a lot of debates in the US around the use of torture in the past few decades, but I feel that there’s been very little public exploration of the ideological work that torture actually does and its direct link to colonial-era projects of reshaping native populations in the image of the colonizer. It also felt important to demonstrate in my essay that the people who prop up justifications for torture and imperial violence are often not the people you would necessarily expect. LGBTQ people, Americans who identify as politically liberal, and human rights organizations are generally not the ones loudly claiming that torture “works.” And yet, the subtly racist things that people write and publish have a significant impact on public perception and the acceptance of inhumane practices as legitimate tactics of war.

2. How have you been able to integrate your interest in women’s studies in the work you have done here at Columbia/Barnard?

As a combined Gender Studies and Human Rights major, I certainly haven’t lacked opportunities to explore the realm of gender studies. However, until I wrote this thesis paper I had never really integrated my two majors together in a substantive way. I took most of the classes necessary to fulfill my human rights major in my first two years at Barnard and have since spent most of my time focusing on gender studies. Because of that, it has actually felt really valuable to return to human rights theory in this thesis paper and to be able to reflect on what I learned from my human rights professors through the lens of transnational feminist critique.

3. What are your plans for the future?

I hope to be able to work in a torture treatment facility in the future. There are quite a few of them in the US and dozens around the world. I did research for a short time at a torture rehabilitation center in La Paz, Bolivia and I’ve interned for a while at the Program for Survivors of Torture at Bellevue Hospital in NYC. I would really like to continue working in that capacity. I’m not sure yet what role I would choose to have in a treatment center, whether as a researcher, an asylum lawyer, or some other function.

1. What inspired you to focus on your topic for this submission?

There are a lot of ways to go about this. Generally, I am very exhilarated by modernism, and I am curious about the ways modernism has conditioned us to think about artistic expression and experimentation. I am also really nourished by the sort of techno-Renaissance I see happening in our current moment in music. A lot of artists are using music technologies really well, in very exciting and complicated ways. But because it’s popular music, the common expectation is that what’s happening isn’t as academic as it really is. My assertion in the paper: it is.

My essay is a far-reaching survey of expressionism, from Schoenberg and the musical expressionists to computer music and contemporary R&B. This is what I call the “long history of musical expressionism,” and the designation is part of my argument. I trace an expressionist treatment of musical technologies from true expressionism through Jean-Claude Risset’s computer music and into contemporary R&B. The contemporary example I take up is Ravyn Lenae and her song “Moon Shoes,” which I think is just brilliant. The heart of the essay is really in Lenae. Lenae’s deeply melismatic style feels evocative of Hildegard of Bingen to me, which carries its own feminist assertions and revivals, but the greater argument that I make is that the current moment in contemporary techno-inflected R&B is a deeply feminist one, primarily charged by the outstanding music of many women of color. The way Lenae and others have embedded deeply complicated (perhaps even deeply expressionist!) techno-musical innovation into popular music is an interrogation of experimentation’s relationship to music, and it’s a rewriting of the white male subjectivity that expressionism once exclusively represented. To me, Lenae’s oeuvre challenges the assumption that techno-musical experiment predicates obscurity, which one might deduce from studying Risset (whom I also love). Another way I could’ve answered this question is by saying that I really, really love Ravyn Lenae’s music. Some real magic is happening in our contemporary moment.

2. How have you been able to integrate your interest in women’s studies in the work you have done here at Columbia/Barnard?

I can’t act like I’m a model scholar of feminist or women’s studies, but as a student of English Literature, I understand that all acts of mediation are acts of power, especially when done in language. Gender is always occultly influencing the ways we speak and write, and the assurance with which one is able to constitute oneself in language. I just finished writing my English thesis on the poet Ariana Reines (a Barnard alumna!), and she takes immense inspiration from Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud had a strategy called the systematic disorganization of the senses, which was concerned with crafting a sense of the poetic “I” by way of undertaking the extremities of human experience—love, suffering, madness; it’s all very immense. Reines has aligned herself with Rimbaud’s strategy in interviews, yet in several reviews of her books that I have read, she would not be applauded for the immensity of her consciousness, but for refusing to shy away from her deepest confessions. So often critics will define female artists by their emotions or autobiographies instead of celebrating their intellectual or artistic prowess. What I’m trying to say is that critics, in all of their manifestations, need to learn how to talk about art made by women in ways that aren’t infused with sexism. We either reinforce or interrogate our current reality depending on which words we choose.

3. What are your plans for the future?

I think I am going to re-read War and Peace this summer. In spring 2021, I will begin a book project at the British Museum as a Henry Evans Fellow. My project is interested in rendering the logic of images, especially Russian iconography, into poetic text.